In 1958 Italian Line started making plans for a large pair of ships to operate in the Genoa-New Your route. Commercial demands were not the only ones to effect the decision to build new ships: a pair of new ships would get new jobs for shipyards, dockers, and most importantly sailors, hence trade unions supported the construction of new ships.

Originally, Italia Line planned their new flagships to be a pair of 35 000 ton liners, only slightly larger than the Leonardo Da Vinci with her 33 000 tons, as to replace aged ships Saturnia and Vulcania, dating from 1927/1928. However, as told before, after reviewing their options on the new ships Italia Line decided to order a pair of true superliners. Their tonnage was to be approximately 45 000 tons, length 275 meters and width 31 meters, making them the biggest pair of Italian liners since the Rex and Conte di Savoia. The new ships were to be slightly smaller in tonnage, they would be longer than their predecessors. The total cost of the ships was about 150 billion Italian Lire of the time, and they were amongst the last ships to be built for the North-Atlantic run.

This decision proved to be a hazardous one from the very beginning. The aeroplane was gathering a larger and larger share of the transatlantic traffic. Even with the Saturnia and Vulcania withdrawn, the ships planned were too large for the route at the time. The Italian Line decided, against all the proof contrary, to go ahead with the construction of the first true Italian superliners in more than twenty years.

When deciding a name for the new ships, Italia line decided to follow a trend they had set by the Andrea Doria, Cristoforo Colombo and Leonardo da Vinci. The ships were to be named after famous historical figures: the elder ship Michelangelo, after the renaissance artist who painted amongst other places the Sixtine Chapel in Vatican. The younger ship was named Raffaello, again after a famous renaissance painter. Both ships had a relief of their namesake artists in their first class lounge and one low-relief in the first class foyer.

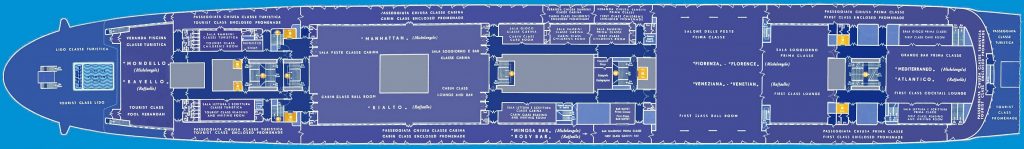

It was decided that the new ships would use the conventional three-class system with different accommodations for passengers of First Class, Second Class (renamed “Cabin Class” because a lot of people didn’t wished to be classified as “second class” travellers) and Tourist Class.

The transported passengers were 1.775: 535 in First Class, 550 in Cabin Class, 690 in Tourist Class, plus 725 crew members, for one amount of 2.500 persons aboard.

The task of building the new ships commenced only within few moths of each other, Michelangelo at Ansaldo shipyards in Genova Sestri, and Raffaello at the shipyard “San Marco”, of C.R.D.A. (Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico) shipyards, in Trieste. Both shipyards were old acquitances to Italian Line. Ansaldo had constructed Roma, Augustus, Rex, Andrea Doria, Cristoforo Colombo and Leonardo da Vinci. CR dell’Adriatico in Trieste had been responsible for the stunning Conte di Savoia in 1933 and in modern times it builds modern cruise ships, such as the Grand Princess of 130.000 tons tonnage, the biggest ship in the world until the recent Queen Mary 2.

The task of building the new ships commenced only within few moths of each other, Michelangelo at Ansaldo shipyards in Genova Sestri, and Raffaello at the shipyard “San Marco”, of C.R.D.A. (Cantieri Riuniti dell’Adriatico) shipyards, in Trieste. Both shipyards were old acquitances to Italian Line. Ansaldo had constructed Roma, Augustus, Rex, Andrea Doria, Cristoforo Colombo and Leonardo da Vinci.

CR dell’Adriatico in Trieste had been responsible for the stunning Conte di Savoia in 1933 and in modern times it builds modern cruise ships, such as the Grand Princess of 130.000 tons tonnage, the biggest ship in the world until the recent Queen Mary 2.

In similar fashion to military ships, the two engine rooms of the ships were complete independent for each other. The aft engine room moved the left screw, by one axle 56 meters long, while the forward engine room moved the right screw with an axle 88,5 meters long. Thus, if one engine room were flooded or under fire, the other could still move one of the screws.

The ships were designed with top speed over 30 knots, but their running speed, due to cost reasons, was to be a more economic 26,5 knots. For the same reason, Italia Line wisely decided not try to take the Blue Ribbon from the American speed-queen United States, since it would have been rather expensive to build and maintain engines that could beat the United States’ record speed of 35.59 knots.

Both of the ships had 30 lounges, one theatre with 489 seats, 3 night clubs, 760 cabins, 18 elevators, a car garage that hosted more than 50 cars, one automatic phone switchboard that connected the internal 850 numbers. There was also a closed circuit TV system for the times when TV transmissions were not receivable from the coast. In the lounges and also on some of the outdoor decks there were input connectors for video cameras, which were used to transmit in the internal TV circuit the images of the various celebrations and parties aboard.

There was also a well-equipped hospital-quality operating theatre and one dedicated division for infective illnesses.

The air conditioning plant had a power of 4 millions b.t.u. power, and the water distiller provided 1 million litres of water for day. 4 steam pipes boilers supplied the steam turbines, which by the power of 85.000 HP moved two screws of almost 6 meters diameter. The rudder weighted 84 tons, its rod was 7 meters long and weighted 33 tons. The hull had a sharp and slender design like in no other ship before and the wheel bridge was almost 76 meters from the tip of the prow.

At early planning stages the new ships took a traditional shape, that of two black-hulled liners with conventional funnels. However, their funnels were soon re-drawn to a never-before-seen shape, based on designs by Professor Mortarino of Turin Polytechnic. These funnels were in fact originally designed for Lloyd Triestino’s ships Guglielmo Marconi and Galileo Galilei, but Lloyd Triestino had opted for a more conventional design. These trellis-style funnels (located far to the aft of the ships), with big smoke deflectors, were much-discussed and criticized during the design phase, as many people though they were horrible in appearance and differed too much from traditional style. In the end they were adopted and gave the ships their unique, unmistakable profile and becoming an effective logo. Scale models of the funnels where long studied and tested in the wind-tunnel of the mechanical university in Torino. The main property of that funnels layout was that they efficiently dispersed almost all the smoke away from the ship.

The hull colour of the new ships was also subject to some debate: black was the traditional hull colour for liners, but it was thought that a white hull might convince passengers that the ships would offer the same level of luxury that the cruise ships that were becoming more and more common on the seven seas. White also showed to be more resistant in the warm Mediterranean climate, thus reducing the need of re-painting the ship.

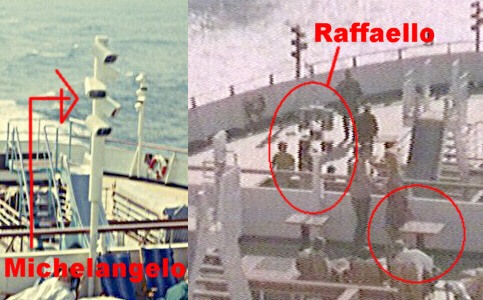

Even though the Michelangelo and Raffaello were planned as identical sisters there were some small differences: the Raffaello was 0.7 meters longer, 0.9 meters narrower and 22 tons tonnage more than her sister.

There were also some purely cosmetic differences: the 1st class lido decks were slightly differently furnished, the Raffaello’s swimming pools had an ornamental and luxurious appearance, while the Michelangelo’s pool was very simple and its lido’s bar had a characteristic triangular shape.

The tables of the lidos of Cabin and Tourist Class were circular on Michelangelo and square on Raffaello. Moreover, the modern lamps (those similar to traffic lights) that lighted the lidos and some outdoor decks were slightly different and painted white on Michelangelo, black on Raffaello.

These are the only few elements which allow to distinguish the ships by outer appearance. The black colour of the top of the aft mast can’t be used as an identification element, since they have been painted over several times, both Michelangelo and Raffaello had it black and white during their few years of service.

Italia Line decided that the new ships interiors, as their exteriors, would be among the most beautiful and luxurious on the high seas. In the spirit of the times, the interior furnishments were made in the Art-Deco style (also known sometimes as Ocean Liner Style, having originated from SS Île de France built in 1927).

The designing of the interiors of the ships were commissioned to different architects. The interiors of the Michelangelo were designed by famous naval architects Nino Zoncada, Vincenzo Monaco and Amedeo Luccichenti, who had already worked on several former ships of the Italian Line. Consequentially the interiors of Michelangelo had a more classical style then her sisters.

The interiors of the Raffaello were designed by architects like Michele and Giancarlo Busiri Vici who formerly had worked only on buildings and created very modern and futuristic designs, prime examples of this were the magnificent first class restaurant and foyer. Probably as consequence the modernist designers, in some other parts the Raffaello’s interiors may look a little more cold or metallic than those of Michelangelo.

Regardless of how they were decorated, the 31 different public rooms for passengers made sure they would not get bored during the long journey.

The restaurants of first and Cabin class extended themselves from “wall to wall” so they spaced trough the full width of the hull. Also the 1st Class main ballroom was extended through the full width of the ship, interrupting the long covered promenade deck. Toward prow there was the 1st class covered promenade deck and toward stern there was those of 2nd class. When required, the two covered promenades could be united, through the ballroom, by opening the glassed doors.

Since the ships took a southern route to New York, it meant that like in the previous Italian liners, much emphasis was placed in the design of the outer decks. There were six swimming pools on the ships, childrens’ and adults’ pools for each class. When the weather turned chilly the first class adults pool was heated by an infrared lamps plant to ensure maximum comfort for passengers. For the first class passengers, there were kennels between the two funnels that even had their own small courtyard, reminiscent of the kennel of the Normandie from 1935.

The only bad thing to be said about the ships is the fact that there were no cabins with windows below the Main Deck. Even thought this made them safer and it contributed to give that slender line to the hull, it proved to be a handicap when the ships entered service, as people were getting used to a high level of comfort, such as cabins with windows. It is also a good remark to remember that all the furnishing and decorations were made exclusively by anti-burning materials. In fact, concerning safety requirements, Michelangelo and Raffaello were quite beyond the safety requirements of that times.

The Michelangelo and Raffaello were the last ships designed for use as pure liners, not as cruise ships and they were the last liners built subdivided in three classes. This allowed the ships to offer a large and economical tourist class for crossings, but made it impossible for the ships to be optimally employed for cruises (them having become a necessity for shipping companies when the aeroplane has effectively taken over the North-Atlantic route by the beginning of the 70’s).

On cruise ships, there was in fact only one class, the first. The Cunard Line solved the problem on the Queen Elizabeth 2 (four years Michelangelo and Raffaello’s junior) by diving the ship in only two classes for crossing, with minimal differences so that they could easily be merged for cruises.

On cruises the ship’s passenger capability was to be limited to 1,200 passengers, because the Tourist class cabins were considered too spartan for by the demanding cruise passengers. Problematic was also the fact that there were no cabins with windows below the A-deck, cabins with windows considered an important thing by cruise passengers (today of course, you need your own verandah instead of just a window). It would have been possible for the Italian Line to rebuild the ships into more cruise-friendly units and ensure their future. It should be taken to account though that construction of these ships in the first place had taken a lion’s share of Italian Line’s funds and rebuilding the ships was financially not an affordable option.